Introduction

My latest artistic research explores how to give the forest a voice – literally! It’s a journey blending art, science, and sound design. Using a special microphone called a geophone, I’m trying to uncover the hidden world of vibrations within trees and soil, translating them into musical forms.

The Geophone: A Window into the Unseen

We often think of sound as something we hear through the air. But vibrations exist everywhere, even in solid objects like trees and the ground. A geophone is a microphone that picks up these subtle vibrations by making direct contact with surfaces. It’s like giving the forest a voice, allowing us to hear its hidden language.

The Journey from Vibration to Sound

Although I utilize techniques similar to sonification, my aim is not merely to represent data. Instead, I strive to create a sonic bridge between the hidden world of the forest and human perception. This involves analyzing the unique characteristics of the vibrations and translating them into sound.

Key Parameters: Amplitude and noisiness

I focus on two main characteristics:

- Amplitude: This is the strength of a vibration. A loud sound has high amplitude, while a soft sound has low amplitude. By tracking amplitude changes, I can understand how the vibrations evolve over time.

- Spectral Flatness: This measures how “noisy” a sound is. A pure tone has low spectral flatness, while a hissing sound (like wind) has high spectral flatness.

The Sonification Process

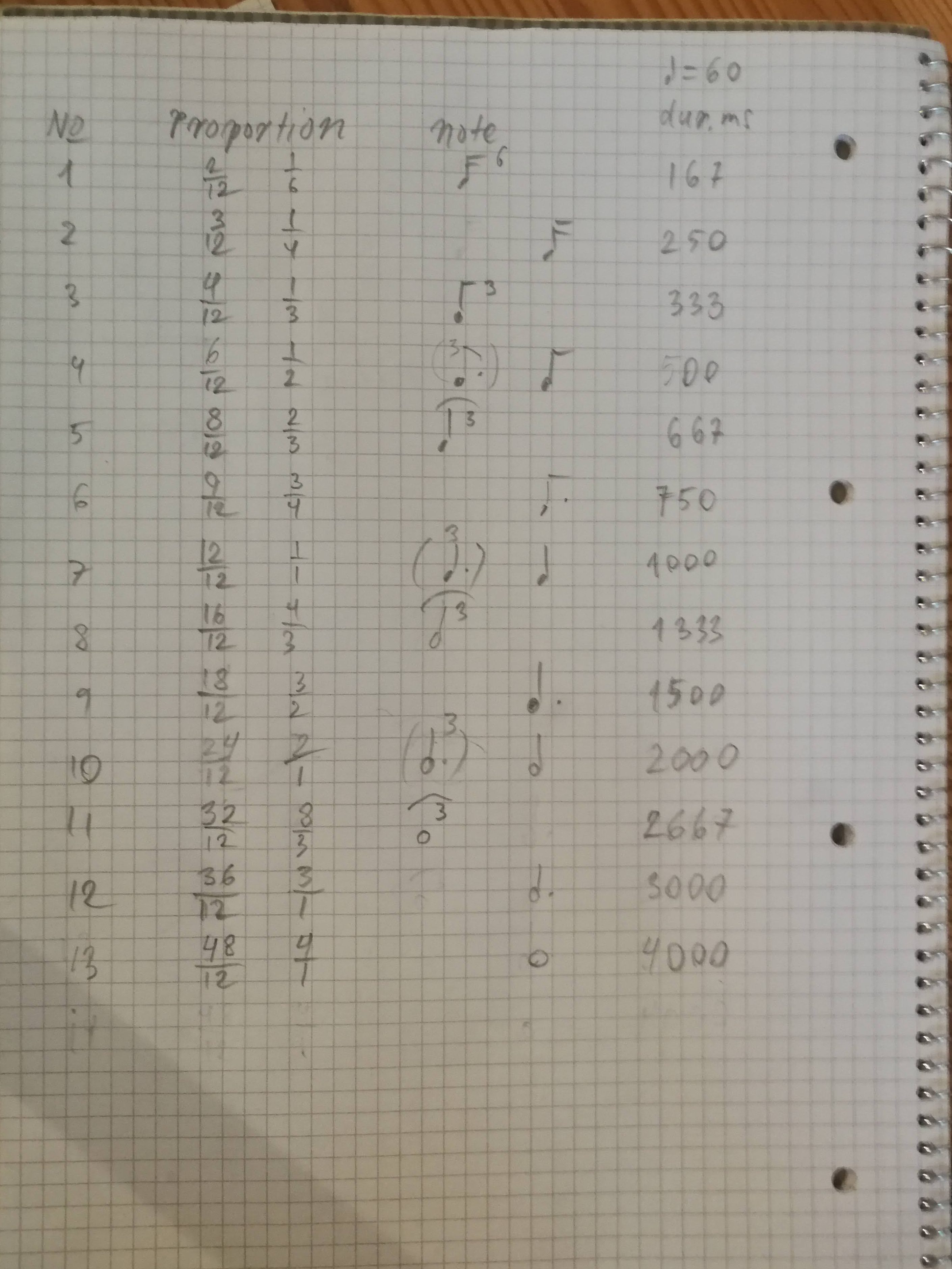

My process involves:

- Dividing the audio into frequency bands.

- Measuring the spectral flatness of each band over time.

- Comparing these values to previously recorded data.

- Triggering musical events based on the differences in the data.

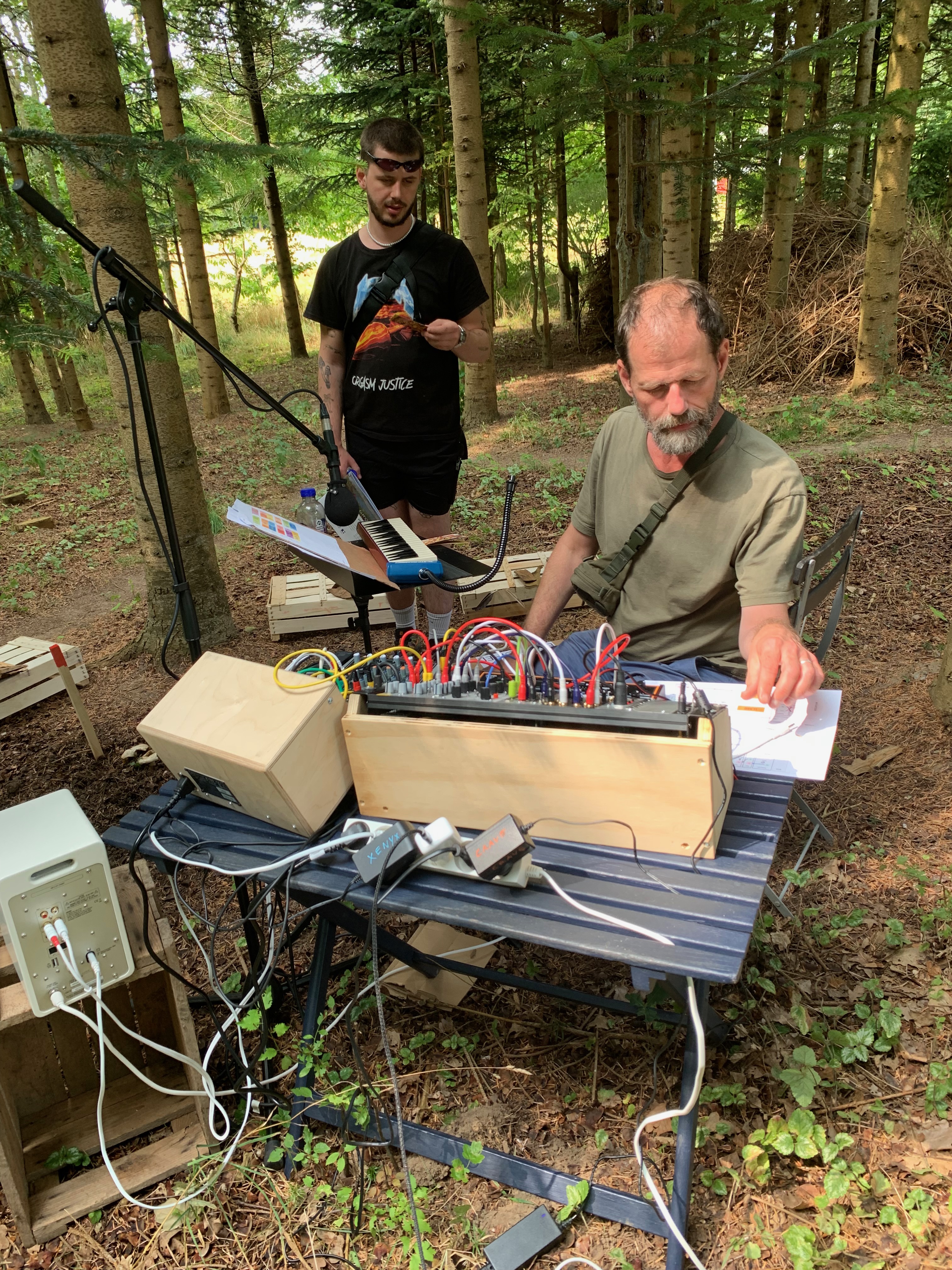

My aim is to create a live concert experience in a forest, where the geophone acts as a conduit for the trees and the earth to participate in the music making. The geophone, placed on a tree or the forest floor, will capture the subtle vibrations of the environment and translate them into triggers for musical sequences. A human musician will then improvise alongside these sounds, creating a unique duet between human and nature.

You can hear an example of how this might sound in this video,

which blends raw geophone recordings with musical interpretation. However, for the live concert, I’ll be taking a different approach, building on my previous work exploring the poetry of Inger Christensen.

A Glimpse into the Unseen

This research seeks to give a voice to the silent language of nature. By revealing the hidden vibrations within trees and the earth, I hope to deepen our understanding of the interconnectedness of all living things.

Conclusion

This is an ongoing journey of exploration, and each recording opens up new possibilities. I’m excited to continue refining this method and uncovering the hidden sounds of our more-than-human kin.

P.S. This blog post has been written with the help of AI