We are nearing our objective of enabling our computer to interact with a live musician in a manner that closely resembles the interaction with another musician. In this fourth vlog, we explore the user interface developed by Samuel Peirce-Davies, which employs the ml.markov object to learn music from MIDI files. Our aim is to extend this functionality to accommodate music played by a live musician, which we’ve found requires certain adjustments.

Specifically, we’ve discovered that the realm of rhythm, or the temporal aspect of music, necessitates a distinct approach beyond the straightforward, millisecond-based logic. The key lies in thinking in terms of PROPORTIONS. Essentially, we’re dealing with the relationship between pulse and rhythm. This relationship needs to be quantized into a limited number of steps or index numbers that can be input into the Markov model.

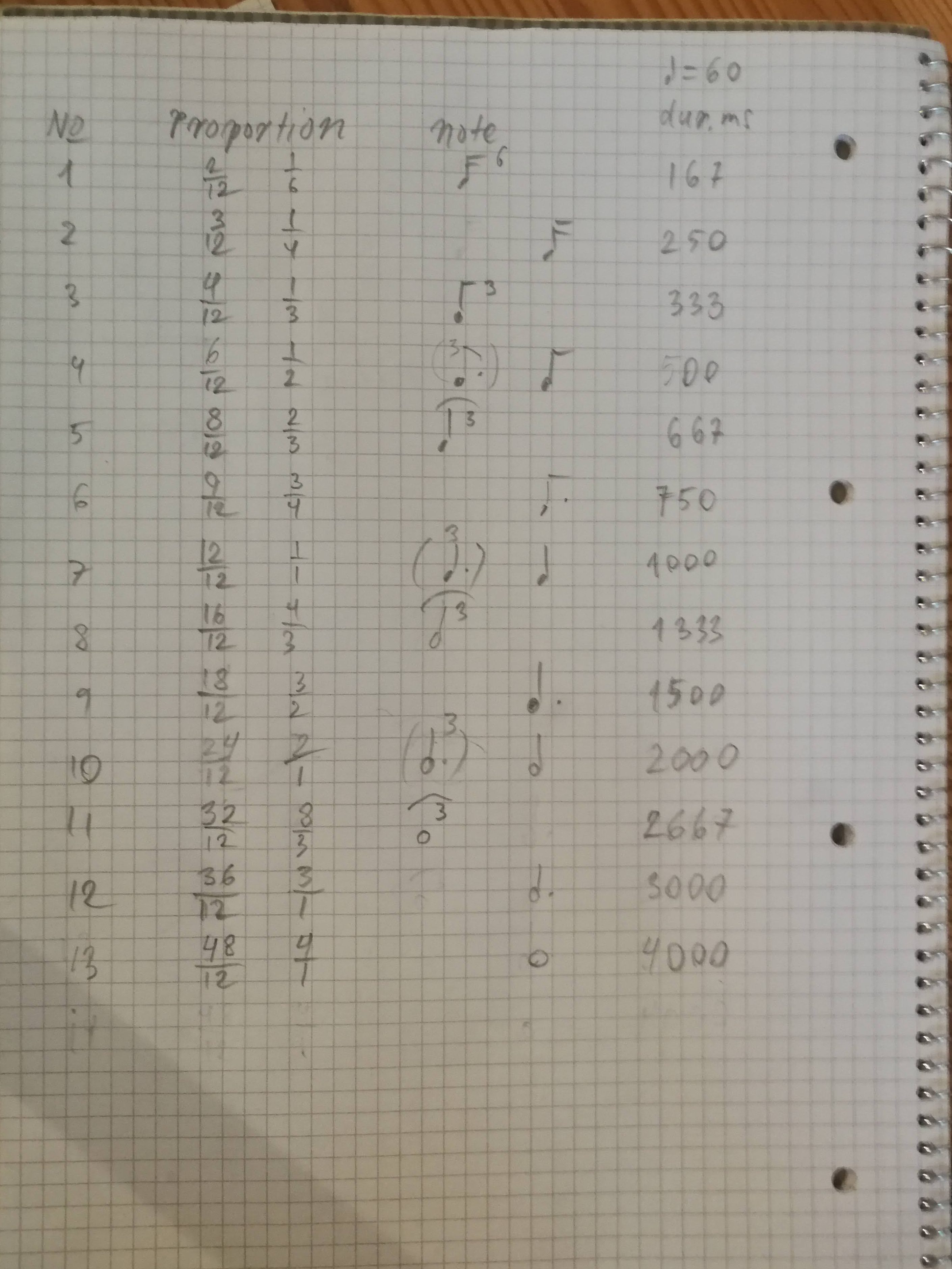

To achieve this, I’ve employed what might best be described as a fractal approach. We’re investigating the interaction between pulse and rhythm, moving away from a linear methodology that divides the pulse into equally spaced steps. Instead, we aim to determine the proportion, leading us to work with a list of fractions that divide the beat into segments like 1/6, 1/4, 1/3, 1/2, and so on.

By setting the maximum rhythmic duration to 4/1 of a beat, we have distilled the complexity down to just 13 different index values. This is in contrast to an equal steps approach, which would yield 48 index values if each beat were divided into 12 equal parts.

Consider whether you would truly notice a difference between a duration of 48/48 versus 47/48. Likely not, which illustrates why 13 index numbers are more meaningful to the Markov model compared to 48. This is especially relevant when considering Samuel’s approach, where any duration, measured in milliseconds, could potentially be integrated into the Markov model.

Sketch to a fractal concept of rhythmical proportions, turning rhythm into 13 index values to be fed into the markov model.

Update, 2024-02-17

After quite some messing around with geogebra, sheets, papir&pencil, I’ve come up with a visual representation of the fractal like structure of the duration index values.

It’s based on the series of duration fractions dividing the beat into triplets and quadruplets following the logic of double value, then dotted value, etc. Here is the series of fractions: 2/12 3/12 4/12 6/12 8/12 9/12 12/12 16/12 18/12 24/12 32/12 36/12 48/12

And here is how these fractions will look when ‘translated’ into squares with a common center:

Notice the self similarity (IE fractal-ness) of the proportion between the blue, pink and brown squares at each level.

If you want a closer look at the maths behind this graphic, here’s the geogebra-patch, I’ve made.

Useful links:

- Samuel’s MAXMSP patches: https://spearced.com/all-downloads/

- Midi files – to use with Samuel’s UI: http://www.piano-midi.de/debuss.htm

- My fractal rhythmic proportions max patch: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1q9fIVVgrr_UbKt1Qv0hvDoOf1vFb7wBl/view?usp=drive_link