See my former two posts in this ‘trilogy’:

Using my body as an analytical tool – is there anybody out there?

Necessary mistakes on the path to an embodied analysis

Read/see/listen more about my methodological reflections here: –>

See my former two posts in this ‘trilogy’:

Using my body as an analytical tool – is there anybody out there?

Necessary mistakes on the path to an embodied analysis

Read/see/listen more about my methodological reflections here: –>

Day one in ethnographic fieldwork into my ethnographic material.

These are my video journals from today, where I document the process of my analytical work:

As you can see in Journal I, above, I have used a logic of parameters to do a pre-sorting of my material. What are the most important factors in play in this specific context? The answer to this question might change as I go along and dig deeper into the material, but for now, there seem to be three overall factors. The first parameter (symbolised by the red cloth) has to do with initiative. The norm is when the adults are setting the agenda. The exception (at least from a quantitative perspective) is when the pupils are deciding what to do and how. Second parameter (grey cloth) has to do with what you can do with your body. The norm is to be sitting on a chair. The exception is when the pupils are alowed not to sit, ie walk, run etc. The third parameter (blue cloth) has to do with being indoor vs outdoors. The norm is being indoors.

Since I had so much space, i chose to represent these three parameters using large pieces of cloth and chairs. An uprigt chair = the norm. An upside-down chair = the exception.

These are the 8 combinations of parameters

To be read this way: image 1: adult initiative, seated, outdoors. Image 2: Adult initiative, seated, indoors. Etc.

For today, I chose the combination BAA, ie: child inititive, seated, indoors. This combination is at play in the situations, where the kids are eating ‘fruit’ everyday from 8.50 to 9.00. I decided to start off my analysis with this combination partly to make things easier for myself. Had it been for example the afternoon ‘own time’ playing sessions, it would have been much longer sound files (up to 1½ hours), and although it would be withing the ‘child initiative’ mode, it would be a mix between seated and freely moving (though not running or jumping). Is this an important distinction? I guess my further analysis might shed some light on that.

So I chose the ‘fruit’ sessions, of which I have 10 recordings, each with a duration of appr 10 minutes. A simple, ritualized activity, with a clear framework for the distribution of time, space and energy (cf Rancière).

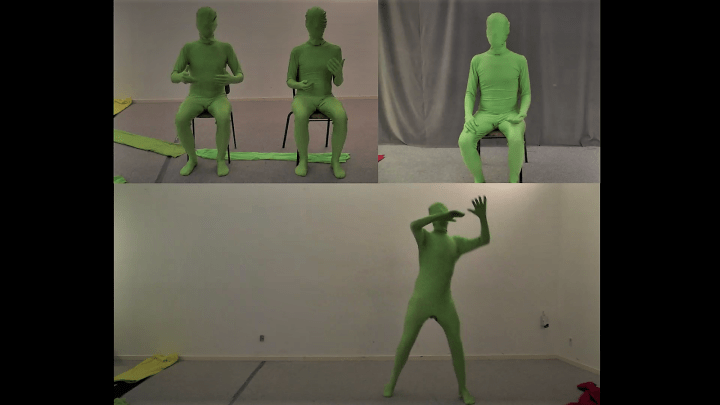

In Journal II, I show some of the results from the experiments. The basic idea is to create a kind of being (using my body ‘masked’ by a green ‘second skin’ suit); this being reacts to certain sounds. I made an easy choice, and decided to divide the sounds according to who made them. I was able to identify the persons from the timbre of their voices, and I selected three children to be represented. For each child I made a video recording of ‘the green being’ gesturing in imitation of the voice of the child. This gave me three individual recordings. I made a fourth recording where the green being incorporated the noise sounds. I combined these four video recordings into one single movie, this way:

Back home, after showing this work to a selected audience (my better half and her friend), with their feedback, I have the following conclusions:

Getting rid of the impersonification of my first attempt, in future attempts, there will be an extra possibility: working with spatiality. The sounds of voices are coming from different places in the stereo soundscape, and this dimension of the soundscape can be extracted by the analyzing body, by moving bodyparts or the whole body in the corresponding direction.

Is this also a one-to-one logic? Maybe. But not in the same sense as above. Representing a specific person by one ‘analytical body-being’ doesn’t ad anything to what the typical language-based analysis is perfectly capable of. We don’t need an embodiment to do that, since we can simply just say: “Peter says ….”.

Basically, what I think I understand now, is that choosing the all too obvious direct impersonification has probably been a necessary step for me to realize, that for my experiments with the body as an analytical tool to make sense, I must abandon the representational stance, and instead take into account the level of materiality, so to speak. In this case – where the material is sound recordings – the materiality of the material consists in sounds and noises developing in time and space.

“I have conducted an ethnographic fieldwork in a public school, in a reception class, with children aged 7 – 9. I now have a lot of empirical material to analyze. I have fieldnotes, sound recordings, some photos etc.

Read more about my studies in Educational Anthropology

I have a question to you, and I need your help

I am going to do a ‘traditional’ ethnographic analysis, where you mostly use language as a tool, using codes, categories, etc.

I would like to use some other methods as well

One method, I would like to try is to use my own body as an analytical tool. What does that mean? It means that I for example listen to a sound recording of children eating fruit during the morning break. By listening to this recording, in a large room, with space for movement, I am going to do a video recording of my movements. This way, I am using my body as an analytical tool in the sense that I listen to the sound from my field recording, and move my body accordingly

I want to do this, firstly because I am interested in movement as a phenomenon. Secondly, I think that by starting the analysis by applying terms, codes and categories there are many important things left out

So my question to you is:

Do you know of anyone who has worked with a similar approach?

Someone who has used movement, maybe dance, or choreography with the analysis of ethnographic data? … or something along these lines

You might wonder why I am standing here.. I am in the Winter Bath. I’ve just been to the sauna and I’m feeling great. It’s a snowstorm. My point by choosing this place is that it makes sense as a place to ask this question about the body and what the body can do, and so on.

Thanks for listening and watching

I hope you will share your knowledge

Now, I’ll jump into the water”

Reflecting on my observations in the reception class (read more about my field study here), I come to think about the pupils and their struggles to come to some kind of grasps with what is expected from them. It’s evident that in this specific context, there are some adults that are trying to make them understand what to do, when and how, but it is not at all evident that the pupils manage to comply. This is probably at play to some extend in a standard class – indeed probably in all social contexts – but it’s my impression that it is very acute in the reception class.

I am thinking about this problem of someone not doing what is expected, and I want to expand on it by drawing on the metaphor of the container. I am not sure, where this text will bring me, but let’s jump right into it, shall we?

In a standard class, composed mostly by kids who have grown up in Denmark, and who therefore probably have a rather clear image about what it means to go to school ‘the Danish way’, when a kid is not doing what is expected, it can probably in most cases be boiled down to a matter of either not being able or not willing to comply. In most cases, I guess that what is being expected is rather clear to everyone involved. To me, a useful way of thinking about these things is to think about them in terms of a game. In the standard class, everyone knows the rules of the game, but each participant play the game more or less well, and with more or less commitment. In the reception class, maybe a lot of what is going on is that the participants think they know the rules of the game, but in actuality, they are playing different games with different sets of rules.

A way to approach this is through Wenger’s theory of legitimate peripheral participation. This is a theory that makes a connection between ‘learning’ and ‘sociality’, and the key idea is that ‘learning’ takes place in an individual in his/her process of becoming a part of the given ‘sociality’. Learning, and in extension establishing social – and I would also add emotional – relations with others, happens, in Wenger’s optics, as you are approaching some kind of social center. In this way, learning and being social are two interdependent parts of the same process, and this process has a clear direction: towards the (social) center.

I think Wenger’s theory can be very useful in describing the processes that are going on in the standard classroom, and to some extend in the reception class as well. The thing about the reception class is that new pupils are starting all the time. In the class I am studying, at my arrival, there were thus 3 new pupils who had started the week before. That is two weeks ago. A new pupil is going to start next week. It would obviously be interesting to ask what happens in these pupil’s process of becoming part of the sociality of the class, and – in extension – acquiring the knowledge and skills needed to be part of a Danish school class.

These are very relevant perspectives, and they are also very useful when it comes to questions like policy making, pedagogy etc. The people involved in the organisation and decision making around the reception class, understood as an institution, of course need knowledge about the processes through which an ‘input’ – in the form of the not-yet competent child – can be transformed into an expected ‘output’ – the pupil who is ready to take part in a standard class.

One of the core elements of Wenger’s theory is the idea of the negotiation of meaning. In the process of ‘approaching the center’, so to speak, the participants are trying to come to some kind of common understanding of what is going on. Returning to the idea of a game, I would translate this into to a process where the participants are negotiating, first, which game their are playing; then they are coming to some kind of agreement about the how the rules of this game should be; finally, they ‘play ‘the game, which entails a whole range of instances of negotiating who breached which rules, in what way, at the expense of whom, etc. This is of course a simplification, and the process is not to be understood as sequential and linear as my description might suggest.

There is a lot more to Wenger’s theory and I might have gotten it all wrong, but nonetheless, if we stick to the idea of school as some kind of game that everyone involved is somehow playing, what is relevant to ask is what this specific activity of ‘playing’ school, Danish style, involves.

In order participate in the game, ‘playing school’, one has to accept the idea of a self, of an individual, and that this self or individual is somehow contained inside a recipient, a body. When ‘playing school’, one will understand that this container, the body with a self inside, is expected to be in certain places, to take certain postures and perform certain movements at certain times and in certain spaces. The default situation is one where the container is kept still and quiet on a chair. (Steen Nepper Larsen writes about this in this article , in Danish, from 2001). Furthermore, if one is joining the game of ‘playing school’, and one is doing it according to the rules, one must accept the idea that the recipient, that contains one’s ‘self’, also is a place that contains a processing device, called a brain, and that this processing device can store what is called knowledge and competences. In other words, one of the goals of the ‘game of school’ is to accumulate knowledge and competences in the individual pupil. According to this logic, the pupil starts out as an empty recepient, and the role of the teacher is to fill up this empty recipient, so that when the pupil leaves school, he or she can be considered a fully competent citizen, ready to be ‘a part of society’.

I want to make clear that what I am saying here is not meant as a critique of the school or the teachers. Rather, I am trying to put words to an analysis based on how people in and around the school talk about and act out the processes through which an ‘individual’ is being ‘educated’.

The idea of the self as a container and schooling as a process of filling up this container with knowledge and competencies is very far from Wenger’s ideology of learning. Indeed, he would probably argue that this ‘container pedagogy’, as we might call it, does not result in learning, at least not in the sense that he understands it. If there is any kind of ‘real’ learning, taking place, Wenger would probably argue that it is not because, but in spite of this pedagogy. However if we see the school through another of Wenger’s central terms, as a community of practice, what this specific community of practice is common about practicing is indeed a pedagogy of filling up containers. This is the game that the participants play, and excelling in this game means doing what’s expected. Doing what’s expected means putting ‘your’ container at the right place at the right time, and controlling what comes in, in the form of images, words etc., and out, in the form of sounds, movements etc., in the expected way. Mastering these competencies is embedded in the social fabric of the school class and its participants, and in this way, Wenger’s theory of legitimate peripheral participation is quite apt for describing what is going on. In spite of it self, so to speak.

What I am trying to get at is that although Wenger himself seems to value certain forms of learning over others, his theory of centrality appears to to be useful in any kind of situation, where there is an institution, – ie. a school or an organisation – in which people are supposed to do certain things. In any institution, the logic of the institution seems to be embedded in the social fabric of the institution itself. Therefore, doing what’s expected will provide you with access to centrality, which means access to social accept, recognition, prestige, etc., as well as to resources, in the form of time, space, money, food, etc.

To sum it up, what I am trying to do here is to describe what I see as a certain logic going on in the Danish way of schooling (and elsewhere). Being a part of the institution of the school implies taking part in a certain game, where a certain idea of the individual and of learning is being played out. You might understand the rules of the game or not. You might accept them or not. You might play the game with more or less excellence. In whichever case you do not have a choice other than being a part of it.

These processes of acceptance, participation, excellence, etc. are rather easy to identify. The people involved are talking about them, and acting and reacting according to them all the time. This is what’s on the agenda of the meetings between teachers, and with school management, with the parents, etc. The pupils who seem not to understand what the rules of the game are, will have to eventually learn them. If this doesn’t happen, it’s because something’s wrong with them, and ‘a diagnosis’ is called for. For those who do seem know the rules, but nevertheless break them, some kind of correctional processes is needed. If this doesn’t help, a psychologist is called for, and in the final ressort, there’s the possibility of expelling the pupil.

These processes are rather commonplace, and a lot can be said, and has been said, not only about what is going on, but also about how the actions involved are reproducing certain forms of power relations, etc.

What I am interested in, and what I am trying to put into words here, has to do with situations in which someone not only does not understand or accept the rules of the game, but where they seem not to have any clue whatsoever as to what is going on. It seems to me that something along these lines is going on for at least some of the pupils in the reception class. And I am wondering if studying these things can help us understand things, among those who do understand and even accept, and maybe support the game, but where there is still some kind of struggle going on.

I think it makes sense to talk about the self as a container as a construction. This implies that other constructions might have been possible. I guess that at this place a full blown scholar would refer to Anthropology as a discipline that confirms this, and he or she would start talking about ‘other possible ontologies’. Or, as Tim Ingold says: “No way of being is the only possible one, and for every way we find or resolve to take, alternative ways could be taken that lead in different directions” (in this talk). I suppose it also makes sense to talk about the process through which one is gradually becoming a part of the logic of the self as a container as a construction. In other words, the (individual) ‘development’ from a (non-competent, empty) child to an adult, who competently manages the logic of the self as a container, or – in Wenger’s terms, from a peripheral learner to a fully competent central actor – is not a development that can be expected to happen naturally in anyone, anywhere. Learning to act according to the logic of the self as a container is also a construction. This process is what a scholar would maybe talk about as a process of civilizing.

There are a lot of things that can be said about these processes, and a lot of critique can be raised about coercion and the relations of power that they engender. There are, however, questions that I can’t find the answer for, when reading these theories. Maybe I haven’t read enough, yet. Maybe Tim Ingold can help me find an answer. I just stumbled across his name in a text i read a few days ago, and for now, my access to Ingold’s thoughts is via videos on YouTube, – and there are many! What I am struggling with has to do with this: One thing is the children in the reception class who seem to be more or less clueless as to which ‘game’ everyone is playing. Maybe this is somehow because they have a ‘theory of self’ which is different from the one that is embedded in the institution. This is one thing. Another thing is the ones who are seemingly playing the game of the self as a container, and playing it ‘well’. It seems to me that even though people are talking about what they are doing in a way that confirms the idea of the self as a container, and even though their words and actions succeed in reproducing this logic, there are still a lot of things going on in and around them that somehow doesn’t fit in. Even for people themselves.

This sounds very abstract, and I would like to try to concretize it more, by bringing in the question of sound. First, however, I think it makes sense to develop a little more on the notion of the self as a container, or rather: alternatives to it. In the talk I am watching on, Tim Ingold is talking about the Inuits and their notion of the soul. In the Inuit language, the word ‘inuit’ is the plural form of the word inuq, which – according to Ingold – means soul. I actually thought ‘inuit’ meant people, so this was new to me. So what does the plural form actually mean? Literally it would translate into ‘souls’. In the way the word is being used, it is often used as an addition to a word for a geographic place, in a way that could be translated as ‘soul life going on in [name of the place]’. Ingold’s point is that for the Inuit it doesn’t make sense to think about the notion of ‘soul life’ the way we usually would in a Western logic, as an accumulation of individual ‘souls’. Here, Ingold goes on to discuss some very complicated things about the relation between part and whole, and I won’t go more into this for now, mainly because it’s too abstract for me. What I do find useful in Ingold’s talk at this place is when he talks about the way the Inuit understand the ‘life of the soul’, as Ingold puts it, which I guess could be corresponding to the Western notion of ‘the self’, or maybe ‘personhood’. For the Inuit, Ingold says, “children are animated by the soul of their grandparents”. This means that adults tend to treat the children with the same kind of reverence that they would treat their parents. It also means, that “….The idea of ‘early years’, as though children were closer to some imaginary point of origin in the process of socialisation therefore makes absolutely no sense. Everyone at any moment is both older and younger than themselves”. (Here)

It seams that my text at this point would take us to a kind of logic where I now start talking about the implications of what we might call the Inuit conception of the self, when compared to what I have described as a conception of the self as a container. Indeed, an pedagogy build on an Inuit conception of self would be completely different, since a pupil, or a ‘life soul’ would not be seen as an empty container to fill up, but rather, maybe, as something that could contribute with something valuable, in and of itself.

It would be really interesting to go more in depth with this thought. For now i will leave it as it is, and instead I would like to develop more on my probably not so clear ideas about ‘what doesn’t fit in’. I don’t think that an Inuit conception of the self is necessarily better than the container conception of the self. Maybe Ingold does. That’s not so much my point anyhow. What interests me here has to do with the way, a conception of self is being played out, whether by Inuits or Westeners. All this talk about soul, life souls and soul life, is maybe making the whole thing sound all religious and metaphysical. This is probably also the way people in general would think when they hear about ‘primitive people’s beliefs’. For us, the Inuit’s are ‘believing’ that souls are ‘reincarnated’ between generations. Our own conceptions of the self, the ego, etc., on the contrary, are – as we see it – based on hard core science. Therefore, in our understanding, when they believe, we know. As I have mentioned above, to me, it is clear that our ideas about the self are constructions, and they are appearing to be real and true, because we have been confirming them over and over again so many times. In this sense, I think that our conception of the self is not less a matter of believe than the Inuit’s notion of a life soul. And conversely, the Inuit’s notion of a life soul is just as ‘scientific’ as our conception of the self. If what I just wrote makes sense, then it would also make sense to say that in the case of the conception of the self I am talking about here as ‘the self as a container’, not only can it be transformed into other conceptions of self, like for instance one that would resemble the Inuit version, and vice versa, but it also means that neither the Western nor the Inuit conception is necessarily better, more true or more real than the other. This is the ‘classical’ social constructivist description, and it helps me getting me somewhat further. However, something’s missing. I guess it lays somehow in the notion of a construction, which for me denotes something that is already done and packaged. As if people were actually a 100 % into the construction they are living by, once they have been socialised into it, and that’s it. In the case of the construction of the self as a container, my intuition is that the people, I am observing in and around the reception class, although they are seemingly completely immersed in the ‘playing school’, in the container-self fashion, a lot of things are going on that seem to point to other conceptions of self, that are spilling over, so to speak, through cracks and fissures in the surfaces of the containers.

So how to dig deeper into these cracks and fissures, through which other conceptions of self are spilling over? I want to try out a model for thinking about these things, that I draw from a commonly tapped source, before I dig into the question of sound.

In The Matrix, there is a scene where Neo is for the first time part of the team of whatever they call themselves, and they are back in the ‘real world’, which is actually a computer generated virtual world. In this scene, the team is inside a building, and Neo sees a black cat, crossing in a hallway. A moment later, he looks back, and sees the exact same cat doing the exact same movements. He mentions this to a fellow team mate, who gets alarmed and starts shouting out orders. A moment later, all the exits of the building are blocked buy brick walls, and the team realizes that they have been caught. The explanation is that what Neo has experienced – what we in our ‘real’ world would term as a deja vu – in the logic of the movie is a sign that whoever it is who are doing the programming in this exact moment are reprogramming the program that they are part of. In this case because they are turning the building into a human trap. As I understand it, it’s a kind of tick, or glitch, that happens maybe because the CPU of the computer is overloaded. (More about deja vu and it’s significance in the Matrix here). What is going on, here, is that something we as spectators know from our everyday life experience, – a deja vu – is being used in the fiction to point to a fissure, an opening that reveals – if we interpret it right – that what we understand as real, what we perceive with our senses, in actuality is a construction.

Taken as a model to think with in connection with the question I am struggling with in this text, this model of a deja-vu-as-a-CPU-glitch needs to be stripped from some unwanted ‘attachments’. The heroes in the universe of the Matrix are obviously a very small handful of very special people, who have somehow managed to wake up and gain access to the true hidden truth behind appearances. This smells a whole lot like Marx’s false consciousness. Here, it might be useful to turn to David Graeber’s reworking of Marx’s theory and talk about partial consciousness. Graeber defines this as “[a theory] in which actors find it almost impossible to distinguish their own particular vantage on a situation from the overall structure of the situation itself. ” (Graeber (2001) An anthropological theory of value, p.60). In other words, I don’t find it fruitful to think about the access to knowledge about ‘what spills over through the cracks and fissures’ as something that only an avantgarde or elite has access to. In my case, this would mean that I, as the Researcher, with some kind of supernatural intellectual power, gained through my contact with some kind of Magical Academia, would be able to outsmart the ordinary folks, who don’t really understand what they are going around doing. I find the notion of partial consciousness much closer to the intuition I have about what’s going on in the field I am studying. Going back to the deja-vu-as-a-CPU-glitch model, it would then be from the position of Neo, that this phenomenon should be understood. Identifying and analyzing the fissures and cracks I am talking about is not, then, something that we need the expert for, but rather it is something that people are being conscious about, somehow, in their everyday lives. Although it’s not something that they are necessarily putting into words, or are acting according to. But it might be present to them, as a feeling, a longing (cf. Tim Ingold).

Now, I finally want to get to the question of sound. Since the beginning of my field study, I have made it clear to the teachers that i would maybe like to do some video recording of the children. My plan was to start by getting acquainted to the place, and to establish a good contact with the kids and adults, in order to, later, maybe introduce the camera.The problem with video is that when I think about setting up a tripod and turning on the camera, I start imagining everyone getting super conscious about it, and I imagine the kids getting super curious about what has been filmed etc. I also know, however, that once the camera is there, people usually rather quickly start forgetting it and begin to behave as if it wasn’t there. However, in this first period, I have done some experiments with audio recording. With a background as a composer, I have listened to a huge number of field recordings in the past. This time, however, since the recordings are part of a different kind of project, I started listened slightly differently to them. I started thinking about what it would mean for the people who are taking part of these activities in the reception class, if they were only to take into account what they perceived through hearing. One of the things, I started listening for, was role people’s individual quality of voice is playing. On the one hand, I noticed that there are voices that – in and off themselves – seem to push the others to respond. There is for example this girl in the class. She is 7 year old, Urdu speaking, and a total beginner in Danish. She has this high pitch voice, a little squeaky, and she speaks in this very fast, singing way. At least in two instances (out of a very limited material), I have noticed another kid imitating her voice, – even though they don’t speak the same language. On the other hand, I came to think about the likeness of voices, and the difficulty in distinguishing between them. Especially when you don’t know them well – and new kids are coming all the time, I remind you. In general, getting access to what is going on, when only listening poses the problem of knowing who does what. It gets even more complicated when we are talking about actions. When hearing a ‘tick tick tick’ from a corner of the room, where 3 kids are sitting it is near to impossible to know who made the sound, and how.

What does this mean? Cutting off the access to visual input is also cutting off access to a lot of information, that we usually draw on, when dealing with everyday life situations. It means that we have a hard time identifying actions, especially those, of course, who do not make a sound. It also makes it difficult to find out who does what and to whom. In other words, accessing a situation by only listening to it means a blurring out of agency and identity.

Going back to my initial thoughts, what is happening to the concept of the self as a container, when we are approaching it with our ears only? What happens, I would argue, is that we are forced to take on an entirely different approach to how we can conceive of what we could talk about as the boundaries between people. The thing is, that is is not meaningful say, that when I make a sound, the sound is in me. Nor is it in you, who are listening to me. I don’t think it makes sense, either, to say that the sound is in between us. Therefore I would say that we are having a hard time insisting on the self as a container, when experiencing the self making itself present as sound. This is also probably why one of the forms of interaction in the classroom that is calling for most correctional attention from the teacher is when someone is making sound when they are not supposed to. The conception of the self as a container seems therefore to be linked with a culture that favors a visual approach to life.

What about the question of agency? Since an auditive approach to everyday life blurs out the exact identification of who did what and how to whom or what, it challenges the idea of a conscious individual self, sitting inside a well defined container, making conscious decisions. It also challenges the idea of the individual pupil as a place where a uniform, centrally orchestrated set of competences, knowledges and skills are supposed to be stuffed. In the reception class, there is a new boy. He is 9 years old, but the teachers have told me that they consider him to be mentally at the level of a 7 year old. Or younger. And that there is probably going to be the need for a diagnosis. This idea is fully compatible with the idea of the self as a container, since there must be some kind of not fully developed self sitting inside this boy, waiting to conform to what’s expected. When considering agency as something that is embedded in a conscious self sitting in a container fenced off, so to speak from other selves, the teachers will focus on the individual actions of an individual pupil. Accessing the world primarily through vision, the tendency will be to focus on movements stemming from what we perceive as an entity in itself, with clear visual boundaries in the form of limbs and body parts attached to an individual body. Accessing the same world auditively, or at least with a more balanced ‘perceptiual mix’, would maybe push focus away from individual agency with a specific individual source, from a center in a specific container self, and open up for a different conception of agency, that we could maybe talk about as distributed or decentral. Playing with this thought, in the case of the going-to-be-diagnosed boy, an approach based on a decentral conception of self and agency would maybe not call for a reaction directed towards an individual boy, contained in a body, identifiable by specific antropometric features. If a reaction would be called for at all.

These were the words for now. I know they were probably too many. If you are still hanging on, however, you might have something to add or comment, which I would highly appreciate. Feel free to write your comments below!

(Continued from: An economy of emotions and actions? Part 1 of 4)

What I am basically trying to do here, is to find a way of talking about the processes through which ‘something new’ comes into being in a collective. I am thinking about all the small interactions, where someone is coming up with something that others will eventually take part in, somehow – or not. And I am in particular thinking about the situations where the people involved come to consider this something, someone has come up with, as valuable, in some sense.

Now, of course in order to pull this project off, there are some questions to raise. First of all, I would have to find out how to know that “something new has come into being”. I would have to find ways of pointing to specific actions that would convey that a process of becoming of some sort is actually taking place. And I would have to find a way of knowing if and how people consider this new practice or pattern of behavior valuable.

Going back to the question of coming up with something, let me develop a little on a concept I would like to talk about as ‘a proposition‘. As I see this process, what happens is that someone comes up with something, whether it be an idea for a collective activity, or a certain way of performing an action that has an implication on the group. Someone is proposing something, and then others can chose to react in whichever way, related to the proposition.

There are three points I would like to go a little into detail with in this regard.

First of all, I would like to make it crystal clear that the concept of proposition that I am developing here, does not necessarily have to do with an individual’s conscious intention. The interesting thing about these processes resides rather in the fact that the act of proposing can take place as a kind of spinoff of collective interaction. I guess I am not alone in having experienced tons of situations, where one is taking part in a collaborative process, and where new ideas seems to be spawning out of the blue, so to speak. Afterwards, it becomes very difficult to point out exactly who came up with what. The concept of proposition, in the sense I am trying to develop here, does not exclude individual intentionality. However, it is my impression that the instances of proposition that eventually will gain more weight and durability in a collective are those who have been developed in a collective process.

Another important point I would like to make has to do with intentionality itself. What I find interesting about these processes of coming up with something new in a collective is that they are not necessarily coming from what we would usually think of as goal oriented behavior. In many cases, new ideas are simply popping up by chance, or because someone made what at that point seemed to be a ‘mistake’. These kinds of generative moments are commonplace in artistic processes, especially in those who involve improvisation. The point I am trying to make is that a proposition does not have to come from some sort of problem solving setup. This doesn’t mean, however that a given let’s call it ‘spontaneously spawned’ proposition can not at a late stage help the collective solve some kind of problem.

The third point I would like to make has to do with the way in which something new pops up. I guess the standard image that one would have in mind while reading what I have said so far would be that a proposition would come in the form of verbal language. Indeed, a proposition could take the form of a spoken phrase. A kid in the reception class might thus choose to put forth a proposition to his schoolmates by uttering the words: “Let’s play superheroes. I am spiderman”. He might also simply start climbing up and down whatever is climbable in the surroundings while shooting imagined cobwebs at everyone else. These two forms of proposition are obviously sharing a lot of traits, and in the unlikely case that both would be present in a given context, it would be interesting to find out whether and how the other people’s reactions to each would differ. The verbal ‘version’ of the invitation calls for some kind of response, imposing a risk for the ‘proposer‘ of being rejected. The nonverbal version of the invitation, on the other hand, might inspire others to join, in a risk-free way, and it might also not be understood as an invitation at all. In any case, it makes sense, I would argue, not to draw a sharp line between verbal and nonverbal when it comes to these kinds of proposition.

The argument can be taken even further. The example above – an invitation to a role play – is of course rather well suited for an interpretation that would point to some kind of human agency. After experiencing the situations described, there is a chance that people observing them would independently come to a conclusion that could be expressed in the sentence: “He invites them to play”. Or: “He acts in a way that they might see as an invitation”. This is because there is a focus on what is going on in the interaction between the people involved. What I would like to do here, is to take the argument further and also include the role that things might be playing in the processes where ‘something new’ is coming up in a collective. Taking into account the role of things, – and this means also including questions of space(s), technologies, clothes, etc. – the concept of proposition I am forging out here would also serve to say something about situations, where something new occurs as a consequence of some kind of interaction between some person(s) and the things around them.

To sum it up, the concept of proposition I am working on here has to do with processes where something new is being introduced in a collective. These are processes stemming from collective interaction – although they are not excluding individual agency. They are occurring spontaneously and by chance, in a way akin to the improvisational forms of art, although they might also be linked with some form of intentionality. They can be expressed through a wide range of modalities: verbal, as well as nonverbal, and they can unfold in interactions between people as well as between people and things.

These will be my conclusions for now on this topic, and I would like to invite you to come with comments, ideas, critique and suggestions below.

The concept of proposition is of course just a first step in these processes that I am trying to understand. The question about what happens after a proposition has been made is the theme for my next blog post, where I will draw in Gebauer & Wulf and their notion of mimesis.

The theoretical framework they are proposing is very useful, I believe, to describe what could be termed the production and reproduction of sociality.

With Gebauer and Wulf, I feel I can come a long way to understand what is going on in the process where a given proposition comes to take root in a collective. In order to try to understand what is going on, when some propositions are being accepted, while others are rejected, it makes a lot of sense to draw on David Graeber’s book “Towards an anthropological theory of value”. This is what I am planning on doing in a fourth blog post.

For now: Please share your thoughts, comments, etc., below, I would sincerely appreciate that!

In a few days, I will be starting off my field study. As you might have read in an earlier blog post (in Danish), as a part of my studies in Educational Anthropology, I am going to conduct a field work study in a ‘reception class’, or in Danish: “Modtageklasse”.

The fundamental question I am asking, here again, is: How do we build collectives? My hope is that the context of the reception class can help me expand and refine this question, and potentially come up with something relevant to say.

A reception class is a special class where the children of newcomers are being placed until the have a level of Danish that enables them to take part in a standard class, with Danish children.

In these classes focus is, according to official policy, on language acquisition, but in the practical everyday life, according to one of my informants, the teachers spend a lot of time and energy on what she labels as ‘opdragelse’, which could be translated to ‘upbringing’, ‘disciplining’ or ‘(moral) education’.

At the place of my fieldwork, I am going to be part of two reception classes, a ‘class zero’ for kids at age 6-7, and a first grade, for kids at age 8 – 9.

The reason why this particular place, or what I would like to call ‘social ecosystem’, is interesting, is because it exists somewhat at the edge of some profoundly rooted practices. From the first day at school, a child brought up in Denmark will already have a pretty clear picture about what it means to ‘do school’. On the other hand, children in the reception class – newly arrived from all over the world – will have all sorts of ideas about ‘doing school’. But they are probably rather clueless when it comes to the specific Danish way of doing things. In the social ecosystem of the reception class, in order for the teachers to ‘do school’ the Danish way, these otherwise firmly rooted practices will have to surface. What is expected from a pupil in a Danish classroom has to be made explicit, somehow.

At the same time, the reception class is – in general – a place where teachers and pupils cannot be assumed to share the same language. So how do the teachers come about making the Danish way of doing school explicit, if they can’t use words? This is the second aspect that makes this particular social ecosystem so interesting to me. In an ordinary class, it can’t be said that processes of making the school’s expectations explicit are completely absent. On the contrary. In my own experience (through my numerous visits as a workshop facilitator), classroom interaction is full of examples of teachers – and pupils themselves – making clear what’s expected. In these cases, however, the preferred channel of communication is verbal language. This doesn’t mean that nonverbal means of expression are absent. The messages conveyed through a look, a facial gesture, a certain tone of voice, etc. are omnipresent. Still, the use verbal language seems to have the final ‘say’ in these contexts. My impression is that in the reception class, things are different.

If you are still with me so far, dear reader, you might sound a lot to you as if I am interested in questions of disciplining, coercion, power, etc. These are obvious questions to raise in an institutional context like the School. Afterall, the kids are not there out of their own choice. They are forced to. They are not the ones deciding what to do, how and when. On the other hand, the teachers themselves are submitted to all kinds of directives, policies, etc., ‘from above’. And so on. And behind, underneath everything, if you – teacher, pupil or policymaker alike – do not comply with what’s expected, the ultimate violence of the State is lurking.

This is all probably very true, and it’s definitely an important aspect of the context I am going to be a part of. However, these questions have been dealt with in a vast quantity of scholarly works already.

What I am trying to say is that, even though these structures of power are present, and even though people are to a large degree submitted to them, there are nevertheless a lot of things going on in the day to day routines that can be said to represent some kind of value to the people involved. Things that the people involved would talk about using words like ‘creativity’, ‘curiosity’, ‘humor’, ‘surprise’, ‘play’, etc.

In sum, what I am thinking about here is a capacity that people – even though they are submitted to structures that they cannot really fundamentally change – have to contribute to the shaping of the contexts they are part of, by coming up with all kinds of what I would call propositions.

Rapidly written impressions from a first day at the conference UNIKE, Copenhagen 15-17 June 2016.

My first positive surprise: I had expected long, compact, academic talks with very little audacity and thinking out of the box. And I had expected to see a homogenous crowd of scholars all focused on furthering their own career. What I actually saw whas a very diverse group of people from all over the world, many of which seeming to genuinely being ready to go all-in to rethink the current paradigm in Higher Education.

Here are some of my take-aways from the day.

Ove K. Pedersen’s opening talk was enlightning, although at times a little repetitive. The basic message he got through to me was about the way that the current transformations in Higher Education throughout the Western world follow parallel tracks although – at the same time – these transformations are happening in nationally unique ways, according to historical aspects in each country. The same transnational trend where universities are being urged to find alternative ressources in public-private partnerships, for instance, is being played out in different ways: partnerships are being created, but there are different national ideas about whom is eligible for being a partner. In what Pedersen terms as a US-Germany model, partnerships are being made between universities and the military industrial complex, and not with think tanks. In the Nordic model it’s the other way around. The difference has to do with the way universities have historically been conceived of in the different countries. In US-Germany, the raison d’être of universities is linked with questions of national security and industrial power, whereas in the Nordic states the link is with policies of national welfare and wellbeing. According to Ove K Pedersen. I guess, the good news is that although winter certainly is coming, it’ll strike us differently according to which kingdom we’re serfs to.

To make a connection with the theme of the UNiKE conference, I think that the perspectives that Pedersen has brought to the table can be summed up to a question of how the universities are to a heavy extend submitted to national agendas. Even in a postmodern, postindustrial – and whatever post- you want to add – globalized world. In order to rethink higher education, if we take Pedersen’s points for granted, there is a need for rethinking the relation to the State and the way in which universities are submitted to these national ideologies, influencing the knowledge production i certain directions.

In other words: can a new kind of university – or any other institutioanlisation of a human activity – be concieved in a way where it would be independent of the State and/or the Industry?

This question is – to my understanding – an underlying subject for the group of scholars engaged in one of the 6 themes of the conference, under the headline “Market driven or open-ended higher education?” After listening to the five presentations – nicely orchestrated according to a classical academic hierarchy, first 3 short ‘vignettes’ by the phd-students, and then two heavily loaded presentations by two ‘real’ scholars – I felt a little betrayed by the title. None of the five presenters spend much energy even on coming up with what they understand by ‘market’ or ‘market-driven’. However, I found the presentations genuinely inspirational.

First, Jan Masschelein’s presentation: ‘Excellence or regard? Reclaiming the university as a site for collective public study’. What can I say? The title alone simply inspires! From my own experience with the art world, I can only say that the tyranny of ‘excellence’ is not only weighing on Accademia. Much of what Masschelein talked about in terms of Higher Education, from the concept of ‘the individualized personal learner’, ‘the individual researcher’, to his establishment of a clear connection between excellence, productivity and competition, the exact same thoughts can be applied to the art world and its educational institutions. Indeed, the same perverting tendencies are at play in art ‘production’, where the concept of ‘excellence’ is hooked up with the notion of the aesthetics of the genius, the lone artist sitting in his ivory tower atelier conceiving godlike, highly original works of art, aimed at an anonymous, but awestrong, mass public, craving for enlightenment.

As an alternative to the individualistic employability and product oriented, excellency ridden higher education, Masschelein envisions an alternative inspired by the Universitas Studii of the middle ages in Europe. I wont go into details with his proposition, and I recommend that you check out this text of Masschelein that he provided for the conference (see reference below). Here are some of the keywords from my notes: open ended, flat hierarchy, imaginative investigation, studium – not bildung, existential questions regarding our common world.

What we – here I am referring to the Summer University initiative – can learn from Masschelein is a suggestion for a model to imitate. What it doesn’t answer is how to organize this, and I am left with a doubt whether this seemingly golden age of academia was actually simply a passtime exclusively accesible for a small class of privileged people.

In her talk entitled “Pedagogies of pluriversality” Sarah Amsler attacked the tendency of the current university for, as she termed it, providing prepacked intellectual commodities. Her presentation was rather fast paced, causing a certain numbing in this listener, and I am therefore not sure that I can refer her ideas as faithfully as I would want. However, here are some of the scraps, I did collect. What I heard Amsler say, is that education as an institutionalized practice has developed in a direction, where it’s simply not sustainable anymore, and we should simply “let the educational ship sink”. In her plead for “other kinds of learning” she talked about ‘unlearning’, ‘counter-hegemonic learning’, ‘epistemic disobedience’, and ‘cognitive and educational justice’. As I didn’t feel completely confident with my own capacity for storing the 500 words per second pace of the presentation, I would rather if I could get access to the presentation on paper before concluding anything substantial. For now, I can just say that the scraps i did collect from the talk really resonate with many of the thoughts I am having myself, in connection with my engagement with ‘the Summer University’. From a perspective of a hands-on approach to this initiative, I think that what we can draw from Amsler is an arsenal of intellectual ammunition (and not prepacked commodities) to think with in our development of a conceptual framework.

As the title of my text insinuates, I would like to challenge the connotation that ‘UNIKE’ calls for. Although there were participants at the conference voicing heretical questions whether we actually need universities at all – answering them immediately in the positive, though – what I felt was a general anxiety. The idea of an open ended university, based on the idea of a hierarchical flattening, and a blurring of the borders between who’s inside – who are undeniably gatekeepers, and undeniably privileged (although increasingly precarious) – and who’s outside. When this discussion is taken exclusively by those who are inside, as is the case at the UNIKE conference, I can’t see the discussion if not in a slight pseudo light. These heretical ideas about university, when proposed by insiders, cannot be understood otherwise than as an existential threat to them. And I can’t help feeling that these discussions will always have a certain hollowness to them. It might not be the organizer’s point, but the uniqueness alluded to in the title of the conference, does it basically have to do with an underlying idea about scholars being unique, and having a special, officially endorsed, access to real knowledge?

To break up this basic contradiction, I believe that a key question has to do with the relation between knowledge and economy. These are the two last letters of the conference’s acronym, and I came to think that there needs to be an ‘S’ added to it. That would kind of destroy the sexiness of it, but ‘UNISKE’ would definitely rule out the elitist suspicion I touched on above. My point is that without rethinking Economy, it doesn’t make much sense to try to rethink Knowledge Economy. What I heard as a refrain throughout the day was a call for more funding, and since the market was unanimously staged as a bad thing, we were left with the State, as a (sole) source for funding. However, – echoing Amsler’s sinking educational ship (quoting to Gustavo Estava)- I simply do not see a possibility for any change towards an economic framework for a new meaningful way to conceive the university based on funding from the State in the near – or far – future. It’s not gonna happen. This is where the ‘S’ comes into the picture. In order to rethink thinking and knowledge, we have to rethink the relationship between the economical and the social. Many of the propositions at the conference pointed towards what I would call a ‘Social Knowledge Economy’. How can we synthesize these propositions into viable alternatives/ parallel structures to the existing way?

Maaschelein (2015) Lessons of/for Europe Reclaiming the School and the University. In Gielen: No culture, no Europe : on the foundation of politics. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Hvad sker der med de gode intentioner om at skabe en bedre folkeskole når de rammer policy og penge? Jeg har netop læst et nyudgivet speciale fra RUC, og jeg har fundet stor inspiration til teoretiske og metodologiske overvejelser. Desværre bliver den teoretiske ramme og den metodologiske tilgang brugt på en skuffende måde, når det kommer til selve arbejdet med empirien.

Specialet hedder Skoleelevers interaktion på tværs af kontekster og er skrevet af Kirsti Astrid Borch Sørensen, som afslutning på en MA i kommunikation på Roskilde Universitetscenter.

Sørensen har i et feltstudie i en 4. klasse undersøgt elevernes læring i forbindelse med et besøg på Experimentarium. Sørensen vil i dette speciale beskrive to processer. Den første har at gøre med elevernes arbejde med at tilegne sig naturfaglig viden gennem arbejdet i klassen og i Experimentarium. Den anden proces har at gøre med Sørensens udvikling af et forslag til et læringsdesign, som skal give Experimentarium input til at forbedre deres tilbud. Det er indforstået, at Sørensen i samme forbindelse hermed vil køre sig selv i stilling til en mulig karriere hos Experimentarium.

Det er ikke svært at få øje på nogle interessekonflikter i denne konstruktion og det er Sørensen da også selv opmærksom på. I de videregående uddannelser er der en generel udvikling i retning af, hvad en tidligere undervisningsminister kaldte ‘fra forskning til faktura’ i en bevægelse mod, hvad kritiske røster taler om som en kommercialisering af forskningen. Sørensen har valgt at tone sit arbejde i retning af en kommerciel anvendelse, og selvom hun slår fast at hun er bevidst om farerne, vil jeg alligevel argumentere, nedenfor, for at hun plumber i.

Jeg har læst Sørensens speciale, fordi hun behandler en problemstilling, som ligger meget tæt op af, hvad jeg selv vil arbejde med i mit feltstudie som jeg starter på i efteråret 2016. Det er særligt hendes fokus på multimodalitet og hendes brug videoobservation som metode som har vækket min nysgerrighed. Jeg har fundet stor inspiration i hendes tekst, og jeg skal med det samme understrege, at selvom jeg vil lægge en kritisk vinkel på nogle af hendes resultater, så har jeg stor respekt for det arbejde hun har lagt i det, og jeg anerkender den kompleksitet, som arbejdet med at skrive et speciale indebærer.

Det er særligt den teoretiske og metodiske ramme, som jeg henter inspiration i, i positiv forstand, mens jeg i selve den måde, som Sørensen kobler teori og empiri via det analytiske arbejde finder en anden slags inspiration, – denne gang med negativt fortegn.

Fra Lave & Wenger henter hun teorier om læring i kontekst, og gennemgår begreber som ‘legitim perifær deltagelse’, ‘meningsforhandling’, ‘tingsliggørelse’ mv. Lave og Wengers læringsteorier er meget brugt i Danmark, i de pædagogiske fag. Jeg synes, der er rigtig mange gode elementer i deres tænkning, og har selv refereret til den i mine hidtidige tekster. Det særligt vigtige i deres bidrag til læringstænkningen er for mig at se, at de bryder med den kognitivistiske forståelse af læring – som noget der foregår inde i et individ – og plæderer for en forståelse af læring som noget der finder sted i en social kontekst – som noget der foregår i en gruppe. Der er skrevet en hel del kritik af Lave & Wengers teorier. Det som de særligt kritiseres for er, at der ikke indenfor denne teoretiske ramme er mulighed for at behandle spørgsmålet om magt. (Se nederst i denne tekst for links til tekster som diskuterer kritikken af teorien om den legitime perifære deltagelse.) Særligt teorien om tingsliggørelse har relevans for Sørensens arbejde, og uden at jeg skal gå meget i detaljer med denne teori kan citere hendes parafrase af Wenger (2004):

Begrebet [tingsliggørelse] dækker over, at noget gøres til et konkret, materielt objekt uden egentlig at være det. Når vi tingsliggør, projicerer vi vores meninger ud i verden, og som følge heraf opfatter vi dem som noget, der eksisterer i verden, og noget der har en ’virkelighed’ i sig selv

For så vidt den metodologiske ramme angår, beskriver Sørensen hvordan man kan bruge videokameraet til at få fat i de multimodale aspekter af elevernes interaktioner, og hun trækker på en længere række tekster, som er rent guf for mig set i forhold til mit fremtidige arbejde. I en reference til Jewitt (2008), beskriver Sørensen, hvordan “forskere ofte negligerer de multimodale og kropslige dimensioner ved klasserumsinteraktioner”. Og det ligger helt på linie med mine egne overvejelser bag det feltarbejde jeg skal i gang med i efteråret 2016. Sørensen benytter sig af en metodik, hun med Cowan kalder multimodal analyse, hvor man i transskriptionen af videoen noterer en længere række parametre. Udover talen noterer man også blikretninger, gestik, mimik, mm. Det som særligt tiltrækker mig ved denne metode er, at den med Cowans ord kan hjælpe os til at “looking beyond the traditionally educationally prioritised linguistic modes of speech and writing” (Ibid.: 19).”

Så vidt den teoretiske ramme og den metodologiske fremgansmåde. For mig har det været rigtig inspirerende læsning, og jeg har fået nogle gode tekster i mit digitale bibliotek, som jeg skal hygge mig med gennem sommeren. Med så meget desto større interesse gik jeg i gang med at læse specialets analytiske afsnit. Men desværre lykkes det ikke for Sørensen at sætte de empiriske fund i spil med teoretiske ramme. Og metodogisk lader det til at hun kunne være nået frem til de samme konklusioner gennem simpel observation og en god gammeldags notebog. Jeg skal forsøge at forklare, hvordan jeg er nået frem til disse konklusioner.

Sørensen har lavet feltstudier i en 4. klasse, både i klasserummet og mens eleverne er på besøg på Experimentarium. I klasserummet har eleverne nogle opgaver de skal løse, hvor de bla. skal finde ud af, hvilke muskler man bruger når man hopper. I Experimentarium har Sørensen observeret to forskellige aktiviteter, som har det til fælles, at deltagerne bevæger sig rundt i og skal handle på en bestemt måde i forhold til nogle lamper der lyser forskellige steder.

Sørensen dykker ned i fire situationer som hun har videofilmet, og lavet multimodale transskriptioner af. I hendes analyse lægger hun meget vægt på elevernes interaktion med objekter, og på den måde de bruger deres kroppe til at ‘forhandle mening’ (i Wengersk forstand). De eksempler hun kommer med er imidlertid ret banale. Hun fremhæver bla. hvordan en elev, i det han nævner en række andre elever, peger på dem med fingeren samtidig. Og et andet tilfælde hvor en elev taler om sin læg, og løfter op i buksebenet og peger på den. Sørensen er også meget inde på, hvordan eleverne ‘tingsliggør’ i de interaktioner de er i gang med. Jeg har en fornemmelse af, at Sørensen strækker dette begreb et stykke længere end det egentlig kan holde til. På en observation hvor en elev står og holder på en væg for ikke at miste balancen, imens hun kigger rundt, bliver væggen i Sørensens analyse ‘tingsliggjort’ i en ‘meningsforhandling’, som pigen er i gang med. Men er eleven ikke bare i gang med at prøve at undgå at falde ned?

Nu er det ikke så meget for bare at kritisere, hvad der lader til at være en uholdbar brug af et analytisk begreb. Det som er kernen i min kritik er, at Sørensen ikke får skabt en syntese mellem empiri og teori, gennem analysen. Hele overbygningen til Wengers teori har at gøre med, hvordan læring finder sted i en social kontekst. Kernebegrebet i hans teori er mening. For at danne mening indgår mennesker i, hvad han taler om som meningsforhandlinger. Og disse bygger på tingsliggørelse og deltagelse. Problemet med Sørensens analyse er, at hun i de fire situationer hun analyserer ikke rigtig får knyttet en forbindelse mellem deltagernes handlinger, og hvordan disse kan siges at være vævet ind i et praksisfællesskab. Sørensen fremhæver tingsliggørelsen som en central modalitet i interaktionerne, men hun får ikke beskrevet hvordan disse tingsliggørelser har eller ikke har en forbindelse til et eventuelt delt repertoire af erfaringer hos deltagerne. Måske er problemet, at der i grunden ikke er tale om praksisfællesskaber, og at eleverne egentlig ikke for alvor deltager. Og at den måde de deltager snarere er i form af parallelle individuelle forløb frem for et fælles samarbejdende meningsforhandlende forløb.

Sørensen får ikke den teoretiske ramme hun har sat op for sit arbejde rigtigt i spil, og som læser savner jeg at se, hvordan de forskellige eksempler, hun analyser kan forståes ud fra spørgsmål om praksisfællesskab, legitim perifær deltagelse osv. Dog finder der givetvis en meningsforhandling sted, og eleverne får løst den opgave der er stillet, og finder for eksempel ud af, at vi hopper ved at bruge lægmusklerne. Men som Sørensen selv er inde på, idet hun citerer Wenger er der ikke nødvendigvis en sammenhæng mellem undervisning og læring. Og vi får ikke noget svar på, hvad eleverne gør ved den information, at deres lægge tjener til at give dem mulighed for at kunne hoppe.

Der er en række aspekter af elevernes interaktioner, som dukker op i Sørensens analyse, men som hun ikke tager fat på analytisk. Der er ret mange eksempler på, hvordan sådan noget som konkurrence og hierarki mellem eleverne har indflydelse på, hvordan de løser opgaverne. Sørensen har ikke etableret et teoretisk beredskab til at behandle disse problemstillinger analytisk. Og de får lov til at svæve i luften.

Det får mig til at tænke på den kritik, Hodgson og Standish (2009) har rejst af uddannelsesforskningen, hvor de peger på det problem at “theory makes an appearance prior to the empirical research ‘proper’ in order to provide, as it were, a stage-set for the study”. Der er med andre ord noget der tyder på at Sørensen har valgt at bruge Lave & Wenger på forhånd, men at empirien har budt på nogle helt andre problemstillinger end dem som denne teoretiske ramme har kunnet belyse.

Spørgsmålet er, hvor det præcis er at kæden hopper af? Er det fordi Sørensen ikke formår at få øje på de aspekter af det empiriske materiale, hvor der rent faktisk er tale om legitim perifær deltagelse, praksisfællesskab, fælles repertoire, osv? Jeg mener, at der er i det empiriske materiale er ansatser til dette, især i forhold til et delt repertoire. Om aktiviteterne på Experimentarium kan det siges at de er meget spilbaserede, og det er jo oplagt at tage den fælles forståelse af fænomenet spil, som de deltagende må formodes at dele, op. Eller er problemet, at Wenger og Laves teorier ikke egner sig til at beskrive centrale processer i den slags situationer, som Sørensen beskæftiger sig med? Som også kritikken af teorien og legitim perifær deltagelse fremhæver (se listen nederst), har denne en udfordring ift. at tage spørgsmål om magt i betragtning. I Sørensens empiri er der tilsyneladende, som jeg har været inde på ovenfor, nogle uomgængelige aspekter af elevernes interaktion som har at gøre med magtbalancen mellem dem.

Uanset hvad der er forklaringen efterlades jeg med en fornemmelse af, at der med det materiale, som specialet har arbejdet med kunne være gået meget mere ind til benet, både på et metodologisk og analytisk plan og med hensyn til anvendelsen.

For det første mener jeg at man med det foreliggende materiale kunne gå meget mere ind i det interaktionelle spil mellem børnene. Jeg tror, at man med videoobservationen kan finde nogle interessante pointer frem, i forhold til hvordan deltagerne forhandler mening sammen. Og det går videre end til blot at pege på de ret oplagte eksempler, hvor en elev peger på en person eller et objekt, imens han nævner det. Jeg tror at for at få ordentligt fod på disse situationer skal vi bruge for en bredere teoretisk ramme, som også kan håndtere spørgsmålet om hierarki og magtforhold.

For det andet kan der med dette materiale peges på hvordan de didaktiske rammer for elevernes interaktioner fremmer visse former for samspil, imens de hæmmer andre. Selvom det kropslige kommer i spil, både i klasserummet og i Experimentarium, kan der i høj grad stilles spørgsmålstegn ved hvilken form for læring der kan finde sted. Netop ved at trække på Wengers teorier om mening, kan man pege på, hvordan eleverne i de beskrevne aktiviteter ikke får mulighed for at forhandle mening i et fællesskab. Det er tydeligt, at de elever som på forhånd mestrer de givne opgaver bedst får lov til at dominere. Eller også får de i forvejen fysisk eller psykisk dominerende elever lov til at styre. Jeg mener, at det er meget tydeligt at der ikke lægges op til decideret gruppearbejde på en hensigtsmæssig måde. Det som skal motivere eleverne til at arbejde sammen er noget udefrakommende. I klassearbejdet forsøger læreren eksempelvis at motivere én af grupperne til at blive hurtigt færdige ved at sige at de andre grupper allerede har afsluttet opgaven. Og i Experimentarium er den for at sige det rent ud helt gal, i denne henseende. Eleverne har tydeligvis ingen fornemmelse af, hvad det læringsmæssige formål med aktivieterne er. De halser rundt, hver især, for at slukke lamper, imens fejl og successer bliver udbasuneret i højttalere. Det er i høj grad ydrestyret motivation der trækkes på, og i forhold til hvilket læringssyn der ligger bag er vi for mig at se slået tilbage til en rent behavioristisk tankegang.

Der er jo ikke sikkert, at Sørensen er enig med mig i disse kritikker, men det er tydeligt for mig, at hun gør meget for ikke at fremstille hverken Ekseperimentarium eller klassearbejdet i et kritisk lys. Hun konkluderer for eksempel på de aktiviteter hun har undersøgt i Experimentarium, at

Et interessant fund i analysen er, at en stor del af eleverne deltager engageret i praksis, når de er på PULS-udstillingen. Det kan tyde på, at eleverne motiveres af den varierende undervisningsform, hvor der i høj grad lægges op til, at eleverne bevæger sig. Hvis det er tilfældet, vil jeg argumentere for, at Experimentariums PULS-udstilling kan være med til at styrke elevernes praksisfællesskaber og deres oplevelse af tilhørsforhold i et fællesskab.

Denne konklusion står for mig at se i grel kontrast til Sørensens beskrivelse af aktiviteterne i analyseafsnittet, hvor det for mig at se fremstår som at at udstillingen fremmer et konkurrence- og præstationsfokus, og netop ikke lægger op til at der arbejdes undersøgende og meningsforhandlende i et fællesskab.

Jeg mener, at der er en tendens i Sørensens arbejde til at glide udenom en egentlig kritik af de praksisser som hun beskriver. Det ærgrer mig, fordi der i den teoretiske ramme og det empiriske materiale ligger en latent mulighed for at samle brikkerne på en anden måde, som ville kunne bidrage med en konstruktiv kritik af praksis, både i klasserummet og i det offentlige museumsrum. Undervisningen i folkeskolen er, som Sørensen også beskriver, underlagt en ramme, som er bestemt af gældende policy, og netop et fokus på det kropslige, det multimodale har for mig at se et stærkt kritisk potentiale. I Sørensens fokus på meningsforhandling og læring i kontekst er der på den anden side et potentiale for en kritik af den didaktik, som udfolder sig i regi af Experimentarium. For hvad folkeskolen fra et policy-perspektiv mangler i forhold til en bredere forståelse af interaktion, som involverer andet end det lingvistisk-kognitive, kompenserer Ekseperimentarium tilsynelandende for ved at inddrage det kropslige. Det er imidlertid en særlig form for kropslighed, der – som Sørensen berører i specialet uden dog at drage denne konklusion – trækker på sportens verden. Og det er en kropslighed som er lagt ind i en konkurrence- og præstationslogik, som virker meget begrænsende for den form for læring, som Wenger og Laves teorier beskæftiger sig med.

Er dette speciale et eksempel på anvendelsesorienteret forskning som underlægger sig begrænsninger for at tækkes modtageren? Eller kommer det til kort af andre grunde? Hvad mener du? Del dine kommentarer nedenfor!

Cowan, Kate (2014): Multimodal transcription of video: examining interaction in Early Years classrooms, Classroom Discourse. Institute of Education, University of London, UK.

Hodgson, Naomi and Standish, Paul (2009) ‘Uses and misuses of poststructuralism in educational research’, International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 32: 3, 309 – 326.

Jewitt, Carey (2008): Multimodality and Literacy in School Classrooms. Kapitel 7. I: Review of Research in Education 2008. SAGE Publications.

Sørensen, K (2016). Skoleelevers interaktion på tværs af kontekster (Speciale. Roskilde Universitetscenter. Roskilde). Find specialet her.

Wenger, Etienne (2004): Praksisfællesskaber – læring, mening og identitet. 1 (3). København: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Kritik ift. Power; as a ‘management ideology of empowerment’; a constructive critique addressing 5 issues, among which social and economic inequalities; overview of the critique including power, trust, predispositions, adding size, etc.

Now that I am about to finish my first year in Educational Anthropology, I begin to see, if not the light, so at least an end to a very busy time, and the beginning of a nice and quiet summer.

Now that I am about to finish my first year in Educational Anthropology, I begin to see, if not the light, so at least an end to a very busy time, and the beginning of a nice and quiet summer.

My original idea was to write on this blog about what I learned while I went to class and worked on my assignments. However, as I begin to see what occupies my thoughts, what I want to share with you is not about the content of my studies, but the very framework that is built around them, ‘here’ in Academia.

Three things have particularly struck me:

First, when I hear my fellow students say that they tend not to take any chances when choosing content and form of their examination papers; they consider who the internal and external examiners are, and commit a significant part of their attention to guess what these two people would prefer. It is important for my fellow students because, if they get a bad grade, they expect this to endanger their opportunities for a career in academia.

Second, when I hear my fellow students (and myself) exit a tutoring session saying “I had a really good idea, but she advised against it, so now I have to find something else to do.”

Thirdly, when I go through a thesis written by former fellow students and I see virtually identical bibliographies and academic questions that are asked and answered in much the same way.

Of course, things are not going on this way every time, I am talking about a tendency.

However, when these situations do occur, I am flabbergasted. Whatever the reason (I suspect a lack of resources and thus lack of time to be a key explanation), it is an expression of the tendency of students not following their academic curiosity. This is because they are either confused, scared, ambitious or because it is unclear what is expected of them or because there are no fixed standards and therefore there are as many ways to write an essay as there are teachers. At the same time, students are told to be independent and to think critically.

Therefore, it was a joy to see that a group of fellow students has initiated what we provisionally called the ‘Summer University’.

The organizers write:

“At the university, students are subject to exams, scoring systems and curricula, which are sometimes simply setting up limits and making people dumber, instead of inviting to contemplation, independent thinking and critical discussion. We would like to create the university we want – and we want to spend our summer on it. Hence the name ‘summer university’. “

My own role in the Summer University is the coordinator of a group that we have so far called the Emergency Management Group. The purpose of this group is to present its ideas to the larger group about the issues that I listed up above, about the frustrations that the students experience in connection with guidance and what I perceive as the limitations on academic freedom.

So far, we don’t have a website, only a closed facebook group.

Please pitch in with your comments below. Do you know of any similar initiatives, that we can learn from? Please share!

En enero – febrero 2016 estoy en la residencia de artistas de la fundacion Lugar a Dudas, en Cali, Colombia.

Durante mi estancia tengo la oportunidad de dar talleres en la Universidad del Valle y el Instituto Departemental de Bellas Artes.

En este video se puede ver estudiantes de música de la Universidad del Valle participando en un taller de composición improvisada en grupo.

Antes del taller di una introducción al marco conceptual:

(Hazle clic al imagen para ver en mas grande)

En mi experiencia hay una tendencia en mis talleres que la gente se divierten mucho. No obstante tengo esta pequeña inquietud que los participantes van a quedarse con eso – el entretenimiento, nada mas.

Con este marco conceptual mi esperanza fue que se den cuenta de lo serio que es ‘jugar’, y cuales son las relaciones con la vida ‘real’ y sus representaciones.

Inspirado por el filosofo francés Paul Ricour, el papel presenta en forma de diagrama la relación entre el campo practico, o la ‘vida real’ con todos sus acciones e interacciones, el orden paradigmático, en qué almacenamos nuestra conocimiento de cuales son las posibles combinaciones de las acciones y el orden syntagmático, qué tiene que ver con las representaciones actuales, es decir las obras de arte, las telenovelas, los narativos, composiciones etc., es decir formas de combinar lo potencial del orden paradigmático en algún tipo de composición que puede influenciar el campo practico de alguna forma, positiva o negativa.

Ver la introducción al marco conceptual: